en.wikipedia

The Boko Haram insurgency began in 2009,[27] when the jihadist rebel group Boko Haram started an armed rebellion against the government of Nigeria.[28] In 2013, more than 1,000 died in the war. The violence escalated dramatically in 2014, with 10,849 deaths.[22][29][30][31] The insurgency has since spread to Cameroon, Chad, and Niger thus becoming a major regional conflict.

The insurgency takes place within the context of long-standing issues of religious violence between Nigeria's Muslim and Christian communities.

Background

Nigerian statehood

Nigeria was amalgamated in 1914, only about a decade after the defeat of the Sokoto Caliphate and other Islamic states by the British which were to constitute much of Northern Nigeria. The aftermath of the First World War saw Germany lose its colonies, one of which was Cameroon, to French, Belgian and British mandates. Cameroon was divided in French and British parts, the latter of which was further subdivided into southern and northern parts. Following a plebiscite in 1961, the Southern Cameroons elected to rejoin French Cameroon, while the Northern Cameroons opted to join Nigeria, a move which added to Nigeria's already large Northern Muslim population.[32] The territory comprised much of what is now Northeastern Nigeria, and a large part of the areas affected by the insurgency.

Early religious conflict in Nigeria

Religious conflict in Nigeria goes as far back as 1953. The Igbo massacre of 1966 in the North that followed the counter-coup of the same year had as a dual cause the Igbo officers' coup and pre-existing (sectarian) tensions between the Igbos and the local Muslims. This was a major factor in the Biafran secession and the resulting civil war.

Maitatsine

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there was a major Islamic uprising led by Maitatsine (Mohammed Marwa) and his followers, Yan Tatsine that led to several thousand deaths. After Maitatsine's death in 1980, the movement continued some five years more.

In the same decade the erstwhile military ruler of Nigeria, General Ibrahim Babangida enrolled Nigeria in the Organisation of the Islamic Conference. This was a move which aggravated religious tensions in the country, particularly among the Christian community.[33] In response, some in the Muslim community pointed out that certain other African member states have smaller proportions of Muslims, as well as Nigeria's diplomatic relations with the Holy See.

Establishment of Sharia

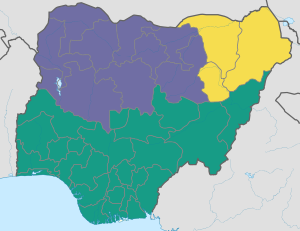

Status of sharia in Nigeria (2015):[34]

Sharia applies in full, including criminal law

Sharia applies only in personal status issues

No sharia

Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Region, as of 14 March 2015

See also: Sharia in Nigeria

Since the return of democracy to Nigeria in 1999, Sharia

has been instituted as a main body of civil and criminal law in 9

Muslim-majority and in some parts of 3 Muslim-plurality states, when

then-Zamfara State governor Ahmad Rufai Sani[35]

began the push for the institution of Sharia at the state level of

government. This was followed by controversy as to the would-be legal

status of the non-Muslims in the Sharia system. A spate of

Muslim-Christian riots soon emerged.In the primarily Islamic northern states of Nigeria, a variety of Muslim groups and populations exist, who favour the nationwide introduction of Sharia Law.[36] The demands of these populations have been at least partially upheld by the Nigerian Federal Government in 12 states, firstly in Zamfara State in 1999. The implementation has been widely attributed as being due to the insistence of Zamfara State governor Ahmad Rufai Sani.[35]

The death sentences of Amina Lawal and Safiya Hussaini attracted international attention to what many saw as the harsh regime of these laws. These sentences were later overturned;[37] the first execution was carried out in 2002.[37]

Blasphemy and apostasy

Main article: Blasphemy law in Nigeria

Twelve out of Nigeria's thirty-six states have Sunni Islam as the dominant religion. In 1999, those states chose to have Sharia courts as well as Customary courts.[38] A Sharia court may treat blasphemy as deserving of several punishments up to, and including, execution.[39][40] In many predominantly Muslim states, conversion from Islam to another religion is illegal and often a capital offence.[41]Demographic balance

According to a Nigerian study on demographics and religion, Muslims make up 50.5% of the population. Muslims mainly live in the north of the country; the majority of the Nigerian Muslims are Sunnis. Christians are the second-largest religious group and make up 48.2% of the population. They predominate in the central and southern part of the country.[42]

For reasons of avoiding political controversy, questions of religion were forgone in the 2006 Nigerian census.[43][44]

History

Main article: Timeline of the Islamist insurgency in Nigeria

2009 Boko Haram uprising

Main article: 2009 Boko Haram uprising

Boko Haram conducted its operations more or less peacefully during the first seven years of its existence.[45]

That changed in 2009 when the Nigerian government launched an

investigation into the group's activities following reports that its

members were arming themselves.[46]

Prior to that the government reportedly repeatedly ignored warnings

about the increasingly militant character of the organisation, including

that of a military officer.[46]When the government came into action, several members of the group were arrested in Bauchi, sparking deadly clashes with Nigerian security forces which led to the deaths of an estimated 700 people. During the fighting with the security forces Boko Haram fighters reportedly "used fuel-laden motorcycles" and "bows with poison arrows" to attack a police station.[28] The group's founder and then leader Mohammed Yusuf was also killed during this time while still in police custody.[47][48][49] After Yusuf's killing, Abubakar Shekau became the leader and still holds the position as of January 2015.[50]

2010 resurgence

After the killing of M. Yusuf, the group carried out its first terrorist attack in Borno in January 2010. It resulted in the killing of four people.[51] Since then, the violence has only escalated in terms of both frequency and intensity. In September 2010, a Bauchi prison break freed more than 700 Boko Haram militants, replenishing their force.

2011

On 29 May 2011, a few hours after Goodluck Jonathan was sworn in as president, several bombings purportedly by Boko Haram killed 15 and injured 55. On 16 June, Boko Haram claimed to have conducted the Abuja police headquarters bombing, the first known suicide attack in Nigeria. Two months later the United Nations building in Abuja was bombed, signifying the first time that Boko Haram attacked an international organisation. In December, it carried out attacks in Damaturu killing over a hundred people, subsequently clashing with security forces in December, resulting in at least 68 deaths. Two days later on Christmas Day, Boko Haram attacked several Christian churches with bomb blasts and shootings.

2012

In January 2012, Abubakar Shekau, a former deputy to Yusuf, appeared in a video posted on YouTube. According to Reuters, Shekau took control of the group after Yusuf's death in 2009.[52] Authorities had previously believed that Shekau died during the violence in 2009.[53] By early 2012, the group was responsible for over 900 deaths.[54]

2013 Government offensive

| This section requires expansion. (September 2013) |

2014 Chibok kidnapping

Main article: 2014 Chibok kidnapping

On 15 April 2014, terrorists abducted about 276 female students from a college in Chibok in Borno state.[57] The abduction was widely attributed to Boko Haram.[58] It was reported that the group had taken the girls to neighbouring Cameroon and Chad where they were to be sold into marriages at a price below a Dollar.

The abduction of another eight girls was also reported later. These

kidnappings raised public protests, with some protesters holding

placards bearing the Twitter tag #bringbackourgirls which had caught

international attention.[59] Several countries pledged support to the Nigerian government and to help their military with intelligence gathering on the whereabouts of the girls and the operational camps of Boko Haram.2014 Jos Bombings

Main article: 2014 Jos bombings

On 20 May 2014, a total of two bombs in the city of Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria,

were detonated, resulting in the deaths of at least 118 people and the

injury of more than 56 others. The bombs detonated 30 minutes apart, one

at a local market place at approximately 3:00 and the second in a

parking lot next to a hospital at approximately 3:30, where rescuers

responding to the first accident were killed.[60] Though no group or individual has claimed responsibility, the attacks have been attributed to Boko Haram.[61]First responders were unable to reach the scenes of the accidents, as "thousands of people were fleeing the scene in the opposite direction". The bombs had been positioned to kill as many people as possible, regardless of religion, which differed from previous attacks in which non-Muslims were targeted. The bombers were reported to have used a "back-to-back blast" tactic, in which an initial bomb explodes at a central location and another explodes a short time later with intent to kill rescue workers working to rescue the wounded.[62]

Escalation in fighting

| This section requires expansion. (March 2015) |

In late 2014, Boko Haram seized control of Bama, according to the town's residents.[65] In December 2014, it was reported that "people too elderly to flee Gwoza Local Government Area were being rounded up and taken to two schools where the militants opened fire on them." Over 50 elderly people in Bama were killed.[66] A "gory video" was released of insurgents shooting over a hundred civilians in a school dormitory in the town of Bama.[67]

On January 3, 2015, Boko Haram attacked Baga and killed up to 2,000 people,[68] perhaps the largest massacre by Boko Haram.[69]

On January 10, 2015, a bomb attack was executed at the Monday Market in Maiduguri, killing 19 people. The city is considered to be at the heart of the Boko Haram insurgency.[70] In the early hours of 25 January, Boko Haram launched a major assault on the city.[71] On January 26, CNN reported that the attack on Maiduguri by "hundreds of gunmen" had been repelled, but the nearby town of Monguno was captured by Boko Haram.[72] The Nigerian Army claimed to have successfully repelled another attack on Maiduguri on January 31, 2015.[73]

Counter-insurgency against Boko Haram

Main article: 2015 West African offensive

Starting in late January 2015, a coalition of military forces from Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger began a counter-insurgency campaign against Boko Haram. [74] On 4 February, the Chad Army killed over 200 Boko Haram militants.[75] Soon afterwards, Boko Haram launched an attack on the Cameroonian town of Fotokol, killing 81 civilians, 13 Chadian soldiers and 6 Cameroonian soldiers.[76] On February 17, 2015, the Nigerian military retook Monguno in a coordinated air and ground assault.[77]On 7 March 2015, Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau pledged allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant via an audio message posted on the organisation's Twitter account.[78][79] Nigerian army spokesperson Sami Usman Kukasheka said the pledge was a sign of weakness and that Shekau was like a "drowning man".[80] That same day, five suicide bomb blasts left 54 dead and 143 wounded.[81] On 12 March 2015, ISIL's spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani released an audiotape in which he welcomed the pledge of allegiance, and described it as an expansion of the group's caliphate to West Africa.[82]

On 24 March 2015, residents of Damasak, Nigeria said that Boko Haram had taken more than 400 women and children from the town as they fled from coalition forces.[83] On March 27, the Nigerian army captured Gwoza, which was believed to be the location of Boko Haram headquarters.[84] On election day, 28 March 2015, Boko Haram extremists killed 41 people, including a legislator, to discourage hundreds from voting.[85]

In March 2015, Boko Haram lost control of the Northern Nigerian towns of Bama[86] and Gwoza (believed to be their headquarters)[87] to the Nigerian army. The Nigerian authorities said that they had taken back 11 of the 14 districts previously controlled by Boko Harem.[86] In April, four Boko Haram camps in the Sambisa Forest were overrun by the Nigerian military who freed nearly 300 females.[88] Boko Haram forces were believed to have retreated to the Mandara Mountains, along the Nigeria-Cameroon border.[89] On 16 March, the Nigerian army said that it had recaptured Bama.[90] On 27 March 2015, the day before the Nigerian presidential election, the Nigerian Army announced that it had recaptured the town of Gwoza from Boko Haram.[91]

By April 2015, the Nigerian military was reported to have retaken most of the areas previously controlled by Boko Haram in North-Eastern Nigeria except for the Sambisa Forest.[92]

In May 2015, the Nigerian military announced that they had released about 700 women from camps in Sambisa Forest.[93][94]

Other issues

Possible causes

The North consisted of Sahelian states that had long had an Islamic character. These were feudal and conservative, with rigid caste and class systems and large slave populations.[95] Furthermore, the North failed until 1936 to outlaw slavery.[96] Possibly due to geographical factors, many (but not necessarily all) southern tribes, particularly those on the coast, had made contact with Europeans - unlike the North which was engaged mainly with the Arab world and not Europe. Due to the system of indirect rule, the British were happy to pursue a limited course of engagement with the Emirs.[97] The traditionalist Northern elites were skeptical of Western education,[98][99][100] at the same time their Southern counterparts often sent their sons abroad to study. In time, a considerable developmental and educational gap grew to appear between the South and the North.[101][102] Even as of 2014, Northern states still lag behind in literacy, school attendance and educational achievement.[103]

Chris Kwaja, a Nigerian university lecturer and researcher, asserts that "religious dimensions of the conflict have been misconstrued as the primary driver of violence when, in fact, disenfranchisement and inequality are the root causes". Nigeria, he points out, has laws giving regional political leaders the power to qualify people as 'indigenes' (original inhabitants) or not. It determines whether citizens can participate in politics, own land, obtain a job, or attend school. The system is abused widely to ensure political support and to exclude others. Muslims have been denied indigene-ship certificates disproportionately often.[104]

Nigerian opposition leader Buba Galadima says: "What is really a group engaged in class warfare is being portrayed in government propaganda as terrorists in order to win counter-terrorism assistance from the West."[105]

Human rights

Main article: Human rights in Nigeria

The conflict has seen numerous human rights abuses conducted by the

Nigerian security forces, in an effort to control the violence, [106] as well as their encouragement of the formation of numerous vigilante groups (for example, the Civilian Joint Task Force).Amnesty International has accused the Nigerian government of human rights abuses after 950 suspected Boko Harām militants died in detention facilities run by Nigeria's military Joint Task Force in the first half of 2013.[107] Furthermore, the Nigerian government has been accused of incompetence and supplying misinformation about events in more remote areas.

Boko Haram often engages in kidnapping young girls for use as cooks, sexual slaves or in forced marriage;[108] the most famous example being the Chibok kidnapping in 2014. In addition to kidnapping child brides, Human Rights Watch states that Boko Harām uses child soldiers, including 12-year-olds.[109] The group has forcibly converted non-Muslims to Islam,[110] and is also known to assign non-Kanuris on suicide missions.[111]

International context

Main article: Global War on Terrorism

The insurgence can be seen in the context of other conflicts nearby,

for example in the North of Mali. The Boko Harām leadership has

international connections to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Al-Shabaab, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s factions, and other militant groups outside Nigeria.[112] In 2014, Nigerian President, Goodluck Jonathan even went so far as calling Boko Harām "al-Qaeda in West Africa".[113] Attacks by Nigerian Islamist militias on targets beyond Nigeria’s borders have so far been limited (as of 2012),[114]

and should not be confused with the activities of other groups (for

example, the responsibility of AQIM for most attacks in Niger). Despite

this, there are concerns that conflict could spread to Nigeria’s

neighbours, especially Cameroon, where it existed at a relatively low

level until 2014, subsequently escalating considerably. It should also

be noted there are combatants from neighboring Chad and Niger.[115] In 2015, Boko Haram swore allegiance to ISIL.[14]On 17 May 2014, the presidents of Benin, Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria and Niger met for a summit in Paris and agreed to combat Boko Harām on a coordinated basis, sharing in particular surveillance and intelligence gathering. Goodluck Jonathan[116] and Chadian counterpart, Idriss Deby[3] have both declared total war on Boko Harām. Western nations, including Britain, France, Israel, and the United States had also pledged support including technical expertise and training.[117][118] The New York Times reported in March 2015 that hundreds of private military contractors from South Africa and other countries are playing a decisive role in Nigeria’s military campaign, operating attack helicopters and armored personnel carriers and assisting in the planning of operations.[5]

See also

Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (1), (2)

| Boko Haram insurgency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Religious violence in Nigeria and the Military intervention against ISIL |

|||||||

The military situation, as of 10 April 2015. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Vigilante groups[4] Mercenaries[5] Supported by: |

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

(2009–2010) (2010–2015) (2015–present) (2007–2009) (2009–11) (2011-present) (2003–2005) (2014–present) (2015–present) (2014–present) |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

130,000 Active frontline personnel and 32,000 Active reserve personnel Nigeria Police Force: 371,800 officers 20,000 soldiers African Union: 8,700 |

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 15,000 killed and one million displaced[22][23][24][25 | |||||||

References

- Boko Haram and the Future of Nigeria, by Dr. Jacques Neriah Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.

Literature

- Johannes Harnischfeger, Democratization and Islamic Law: The Sharia Conflict in Nigeria (Frankfurt am Main 2008). Campus Verlag. ISBN 3593382563

- Philip Ostien & Albert Dekker (2008). ""13. Sharia and national law in Nigeria", in: Sharia Incorporated: A Comparative Overview of the Legal Systems of Twelve Muslim Countries in Past and Present". Leiden University Press. pp. 553–612 (3–62).

- Karl Maier (2002). This House Has Fallen: Nigeria in Crisis (illustrated, reprint ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 9780813340456.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: Riots in Nigeria kill nearly 400 |

- Boko Haram Fighting for their Last Territorial Stronghold, 23 April 2015

- Blench, R. M., Daniel, P. & Hassan, Umaru (2003): Access rights and conflict over common pool resources in three states in Nigeria. Report to Conflict Resolution Unit, World Bank (extracted section on Jos Plateau)

- Understanding the Islamist insurgency in Nigeria, 23 May 2014 by Kirthi Jayakumar.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου