Contents[hide] |

Background

Colonial history

When the European colonial powers met to divide Africa among themselves, the area now known as Somalia was divided between the British, the Italians, and the French. During World War II, Italian Somalia was combined with Ethiopia within Italian East Africa. Italy briefly occupied British Somaliland in 1940, but a year later the British had occupied Italy's territory. After the war, Italy continued to administer Italian Somalia under a United Nations mandate until internal autonomy was granted in 1956. In 1960, the British and Italian territories both became independent and merged as the United Republic of Somalia. The French territory became independent as Djibouti in 1977.

Independent Somalia had to integrate two territories that had been governed by different colonial powers. This meant that two different legal systems were in place and two different colonial languages were used for official business, with Somalis in the one of the two former colonies unfamiliar with the languages of the other. Somalis themselves, though, speak a common language.

Border disputes took place between Somalia and Kenya in 1963 and with Ethiopia in 1964. This second dispute led to armed conflict. Somali irredentism lay behind these wars, the desire to "rejoin lost territories to the motherland." In the post-colonial space, Somali live in five different political jurisdictions.[1] However, armed conflict was in the main absent for the first 17 years of independence, from 1960 until 1977. The idea that Somalis ought to live in a single political jurisdiction can itself be identified as a European type of nationalism. From 1977 until 1991, three conflicts took place: War with Ethiopia (1977-78); civil war in the North-west between the military and the Somali National movement (SNM} over control of that region; internal conflict between government forces and clan-based liberation movements (1989-1990). Following nine years of civilian government, a military coup in 1969 brought Siad Barre into power. A peace accord was signed with Ethiopia in 1988. As well as nationalizing industries, Barre filled government appointments with members of his own Marehan clan while excluding others.

Barre deliberately played different clans off against each other in order to divert attention away from the countries economic problems.[2] He also outlawed reference to clan allegiance, which had the effect of "pushing reference to such identity underground."[3] His increasingly divisive and oppressive regime sparked the internal revolts that led to his overthrow in 1991 and the unilateral declaration of independence by the former British colony as the Republic of Somaliland. Although this entity does not enjoy formal recognition, it remains the only part of Somalia where any effective government is in place. Barre's regime was propped up with military aid from the Soviet Union, which to some extent made Somalia a venue for Cold War politics as the Western states also provided aid.[4] Clarke and Gosende argue that once the Cold War ended, the powers lost interest in propping up Barre's regime in the name of stability and that "when Somalia collapsed in 1991, few people seemed to care."[5] They ask, however, if Somalia ever properly constituted a state, since "Somalia is a cultural nations but it was never a single, coherent territory."[6] On the other hand, the state's constitution made working for the reunification of the Somali people a goal of government.[7] Woodward says that in the 1969 election, all parties were clan based and that already democracy was fragile, being replaced by "commercialized anarchy."[8] Most Somalis are of the same ethnicity. The clans, which are based on lineage, represent traditional organizational systems.

Downfall of Siad Barre (1986–1992)

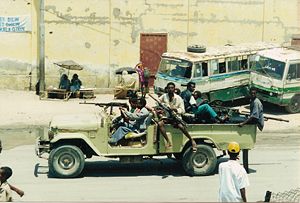

The first phase of the civil war stemmed from the insurrections against the repressive regime of Siad Barre. After his ousting from power, a counter-revolution took place to attempt to reinstate him as leader of the country. Only Somaliland, which comprises the northwestern section of the country (between Djibouti and the northeastern area known as Puntland (which is also effectively independent) have functioning governments. The rest of the country, especially the South, descended into anarchy. Warlords emerged who controlled small zones and competed with each other for domination of larger areas. Taking place in one of the world's poorest countries, mass starvation followed.

International intervention (1992-1995)

United Nations Security Council Resolution 733 and Resolution 746 led to the creation of UNOSOM I, the first mission to provide humanitarian relief and help restore order in Somalia after the dissolution of its central government.

UN Security Council Resolution 794 was unanimously passed on December 3, 1992, which approved a coalition of United Nations peacekeepers led by the United States to form UNITAF, tasked with ensuring humanitarian aid being distributed and peace being established in Somalia. An estimated 300,000 died of starvation during the first year of the civil war. The UN humanitarian troops landed in 1993 and started a two-year effort (primarily in the south) to alleviate famine conditions. U.S. President George H. W. Bush had reluctantly agreed to send U.S. troops to Somalia on what was intended to be a short-term humanitarian mission; they were to "end the starvation and leave."[9] His successor, Bill Clinton, was persuaded by the UN Secretary-General to extend the mission in order to re-establish civil governance in Somalia. U.S. troops remained as the "backbone of the UN mission" alongside smaller contingents.

For many reasons, not least of which were concerns of imperialism, Somalis opposed the foreign presence. At first, the Somali people were happy about the rations the UN and U.S. troops brought them but soon came to believe that the latter were out to convert them from their religion. This idea is thought by some to have been introduced by the warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid. His capture was the main objective of the U.S. contingency. In the period between June and October, several gun battles in Mogadishu between local gunmen and peacekeepers resulted in the death of 24 Pakistanis and 19 U.S. soldiers (total U.S. deaths were 31), most of whom were killed in the Battle of Mogadishu, October 3, 1993. 1000 Somali militia were killed in that battle. The incident later became the basis for the book, Black Hawk Down by Mark Bowden and of the Jerry Bruckheimer-Ridley Scott movie of the same name, and for William Cran-Will Lyman PBS documentary, Ambush in Mogadishu. Two U.S. Blackhawk helicopters were shot down and U.S. soldiers were chased through the streets of Mogadishu. These scenes were broadcast across the world. Public reaction in the U.S. led to the total withdrawal of U.S. troops on March 25, 1994.[13] Public opinion in the U.S. could not tolerate military casualties in a war people did not understand in a place about which they knew very little. U.S. troops suspected that Italian soldiers were tipping off Somalians in advance of U.S. attacks.[14] Much of the humanitarian aid was looted, diverted, and sold, failing to reach those who needed help. By controlling how the food was distributed, the various warlords were able to strengthen and maintain their power in the regions they dominated. As U.S. troops tried to track down and capture Aidide, they were unaware that former President Jimmy Carter was engaged on President's Clinton's behalf in peace negotiations with the same warlord.[15] The whole UN mission left on March 3, 1995, having suffered more significant casualties. Order in Somalia still had not been restored. No government was in place that could claim to be able to control the state.

Intervention after 1995

The UN set up an office in Kenya to monitor the situation in Somalia. Somali distrust of U.S. and other non-African intervention shifted the focus onto finding Africans who would take a lead. The idea of delegating more responsibility to the African Union developed, with the UN encouraging and advising but not taking the leading role. Djibouti's President, Ismail Omar Guellah proposed a peace plan in September 1999. However, the main responsibility has been ceded to the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development, a body which has been described as "incompetent and divided."[16] In March 2000, he convened a meeting of Somali intellectuals, who advised in their private capacities on a peace plan. It was this initiative that led to the creation of a Transitional Government later that year. However, this government, which has tried to include all parties and to identify how a more just and equitable political and economic system can be developed, has not established effective control over the country. Unilaterally declared states have continued to assert autonomy, dividing Somalia. Shawcross says that Somalia has become "a geographical expression" rather than a state.[17]

Division of Somalia (1998-2006)

The period of 1998–2006 saw the declaration of a number of self-declared autonomous states within Somalia. Unlike Somaliland, they were all movements of autonomy, but not outright claims of independence.

The self-proclaimed state of Puntland declared "temporary" independence in 1998, with the intention that it would participate in any Somali reconciliation to form a new central government.

A second movement occurred in 1998, with the declaration of the state of Jubaland in the south.

A third self-proclaimed entity, led by the Rahanweyn Resistance Army (RRA), was set up in 1999, along the lines of the Puntland. That "temporary" secession was reasserted in 2002. This led to the autonomy of Southwestern Somalia. The RRA had originally set up an autonomous administration over the Bay and Bakool regions of south and central Somalia in 1999. The territory of Jubaland was declared as encompassed by the state of Southwestern Somalia and its status is unclear.

A fourth self-declared state was formed as Galmudug in 2006 in response to the growing power of the Islamic Courts Union. Somaliland is also seen as an autonomous state by many Somalis even though its natives go another step in pronouncing full independence.

Also during this period, various attempts at reconciliation met with lesser or greater measures of success. Movements such as the pan-tribal Transitional National Government (TNG) and the Somalia Reconciliation and Restoration Council (SRRC) eventually led to the foundation, in November 2004, of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG). However, warlord and clan-based violence continued throughout the period and the so-called national government movements had little control over the country at the time.

Rise of the ICU, war with the ARPCT, TFG, and Ethiopia (2006–present)

In 2004, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was founded in Nairobi, Kenya. Matters were still too chaotic inside Somalia to convene in Mogadishu. In early 2006, the TFG moved to establish a temporary seat of government in Baidoa.

During the early part of 2006, the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism (ARPCT) was formed as an alliance of mostly-secular Mogadishu-based warlords. They were opposed to the rise of the Sharia-law oriented Islamic Courts Union (ICU), which had been rapidly consolidating power. They were backed by funding from the U.S. CIA.[18] This led to increasing conflict in the capital.

Height of ICU power

By June 2006, the ICU succeeded in capturing the capital, Mogadishu, in the Second Battle of Mogadishu. They drove the ARPCT out of Mogadishu, and succeeded in persuading or forcing other warlords to join their faction. Their power base grew as they expanded to the borders of Puntland and took over southern and middle Jubaland.

The Islamic movement's growing power base and militancy led to increasingly open warfare between the Islamists and the other factions of Somalia, including the Transitional Federal Government (TFG), Puntland, and Galmudug, the latter of which formed as an autonomous state specifically to resist the Islamists. It also caused the intervention of Ethiopia, who supported the secular forces of Somalia. The ICU allegedly obtained the support of Ethiopia's rival, Eritrea, and foreign mujahideen, and declared Jihad against Ethiopia in response to its occupation of Gedo and deployment around Baidoa.

Ethiopian intervention and collapse of the ICU

In December 2006, the ICU and TFG began the Battle of Baidoa. Fighting also broke out around the Somali town of Bandiradley in Mudug and Beledweyn in Hiran region. The ICU aimed to force the Ethiopians off Somali soil. However, they were defeated in all major battles and forced to withdraw to Mogadishu. After the brief final action at the Battle of Jowhar on December 27, the leaders of the ICU resigned.

Following the Battle of Jilib, fought December 31, 2006, Kismayo fell to the TFG and Ethiopian forces, on January 1, 2007. Prime Minister Ali Mohammed Ghedi called for the country to begin disarming.

U.S. intervention

In January 2007, the United States officially intervened in the country for the first time since the UN deployment of the 1990s by conducting airstrikes using AC-130 gunships against Islamist positions in Ras Kamboni, as part of efforts to catch or kill Al Qaeda operatives supposedly embedded within ICU forces. Unconfirmed reports also stated U.S. advisers had been on the ground with Ethiopian and Somali forces since the beginning of the war. Naval forces were also deployed offshore to prevent escape by sea, and the border to Kenya was closed.

Islamist insurgency and reappearance of inter-clan fighting

No sooner had the ICU been routed from the battlefield than their troops disbursed to begin a guerrilla war against Ethiopian and Somali government forces. Simultaneously, the end of the war was followed by a continuation of existing tribal conflicts.

To help establish security, a proposed African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) was authorized to deploy as many as 8,000 peacekeepers to the country. This mission widened the scope of countries that could participate over the earlier proposed mission led by the Horn of Africa-based nations of IGAD. The Islamist group leading the insurgency, known as the Popular Resistance Movement in the Land of the Two Migrations (PRM), vowed to oppose the presence of foreign troops.

Legacy

The loss of life of UN and U.S. soldiers, together with the lack of an obvious solution to the internal problems of Somalia, led many critics to conclude that peacekeeping can only be effective in situations where "all parties to a conflict sought to end it and needed the good offices of a neutral force to reinforce mutual trust or verify the fulfillment of obligations."[19] Post Mogadishu, the U.S. in particular has been very reluctant to commit troops to situations where there are multiple competing forces. Instead, an unofficial policy of standing back while one side begins to emerge as the victor appears to have informed subsequent U.S. and UN approaches to several conflict situations. Muravchik suggests that in Bosnia during the Bosnian War, the UN and the U.S. thought that the "shortest path they could see to … an outcome was for the weaker party to surrender."[20] The problem with this approach in Somalia is that there are far too many competing parties for any one to emerge as the overall victor. Boutros-Ghali called it "a war of all against all."[17] An immediate result of the "Somalia misadventure" was international reluctance to intervene during the Rwandan Genocide. The Clinton administration even instructed official spokespeople to avoid using the word "genocide," because recognition of this would trigger intervention under treaty obligations. In Rwanda, Bosnia, and Somalia, the conflicts were attributed to "ancient animosities." Brown suggests that governments dealing with conflict between different communities also play the "ancient animosity" card because it gives "communal violence … the appearance of a natural phenomenon which outsiders have no right to condemn and no hope to prevent."[21] Kieh says that ancient animosity is overplayed as an explanation for conflict in Somalia and elsewhere in Africa, that the colonial legacy played a role as did Barre deliberate provocation of community conflict in Somalia.[22] Colonial powers often pursued divide and rule policies that pitted communities against each other, sometimes building on rivalries that did exist but often finding ways of creating these. Their continued role as peacekeepers could therefore be justified, or so they thought.

What has been called "compassion fatigue" has also had a negative impact on international response to the ongoing humanitarian crises in Somalia. There are "just too many catastrophes happening at once" so people, the media, and governments switch off.[23] The debacle in Somalia has also led to a more jaundiced view of humanitarian intervention. Many people now say why help when the effort is not appreciated. Indeed, as a result of U.S. soldiers going to Somali, many Somalis now regard the U.S. as another colonial power and are suspicious of U.S. motives. Former President Carter stated, “the United States has become the hated enemy."[24] On the one hand, there is no doubt that warlord and clan rivalry was part of the way of life in the Somalian region for many centuries before European rule began. On the other hand, these clans lived in much smaller political polities, under their local Emir or chief. Under colonial rule, these different communities did not need to cooperate or consider the good of the whole nation; governance was in the hands of the colonial power. By choosing to focus on ancient animosities and on inter-clan rivalry as the cause of conflict, the Western analysis "obscures the more long-term failure of the Western model of the nation-state to take hold in the region."[22] There is no doubt, however, that clan loyalties are strong. The problem, though, is not the clan system as such but when different clans are competing for the same slice of the pie. Before the different clans were lumped together in the same state, each clan has their own pie, even if they sometimes coveted their neighbors larger pie. Only an equitable distribution of resources across all the communities will bring an end to this type of envy. The legacy of the Somali Civil War suggests that the international community needs to re-think the idea that the nation-state is always the ideal system of political organization. Power-sharing is likely to be one of the solutions that will be explored in Somalia. This successfully brought an end to a civil war in neighboring Djibouti, once part of the Somalian space. The same strategy has been used in Northern Ireland and in Bosnia. Increased hostility towards the West in Somalia and elsewhere in Africa has placed more and more responsibility on the African Union to represent the UN in African peace-keeping. However, the African nations lack the financial resources to engage in large scale, long term missions. On the one hand, the UN wants to delegate responsibility but on the other hand its richer members have been reluctant to fund this. This has attracted criticism that the international community has effectively decided to stand on the side-line while "Somalia bleeds."[16]

Notes

- ↑ Clarke and Gosende (2003), 135.

- ↑ Kieh and Mukenge (2002), 26.

- ↑ Woodward (1996), 68.

- ↑ Clarke and Gosende. (2003), 130.

- ↑ Clarke and Gosende (2003), 131.

- ↑ Clarke and Gosende (2003), 133.

- ↑ Mayall. 1990. page 60.

- ↑ Woodward (1996), 67.

- ↑ Muravchik (2005), 29.

- ↑ Steve Kretzman, Oil, Security, War The geopolitics of U.S. energy planning, Multinational Monitor. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ Mark Fineman, The Oil Factor In Somalia; Four American Petroleum Giants Had Agreements With The African Nation Before Its Civil War Began. They Could Reap Big Rewards If Peace Is Restored, Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ Ibrahim Hirse, Abdillahi Yusuf’s Transitional Government And Puntland Oil Deals, Somaliland Times. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ History Channel, March 25, 1994 Last U.S. troops depart Somalia, This Day in History. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ Muravchik (2005), 30.

- ↑ PBS, Frontline: Ambush in Mogadishu. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Abdullahi Ahmed Barise and Afyare Abdi Elmi, Civil war: Standing on the sidelines as Somalia bleeds, International Herald Tribune. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Shawcross (2000), 86.

- ↑ Saeed Shabazz, UN trying to clarify problems in Somalia, The Final Call. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- ↑ Muravchik (2005), 33.

- ↑ Muravchik (2005), 26.

- ↑ Brown and Karim (1995), vii.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Kieh and Mukenge (2002), 73.

- ↑ Moeller (1999), 11.

- ↑ Boutros-Gali (1999), 104.

- Ali, Taisier Mohamed Ahmed, and Robert O. Matthews. 1999. Civil Wars in Africa: Roots and Resolution. Montreal, CA: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773517776.

- Boutros-Ghali, Boutros. 1999. Unvanquished: A U.S.-U.N. Saga. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 9780375500503.

- Bowden, Mark. 1999. Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. New York, NY: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 9780871137388.

- Brown, Cynthia G., and Farhad Karim. 1995. Playing the "Communal Card:" Communal Violence and Human Rights. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 9781564321527.

- Bruckheimer, Jerry, Ridley Scott, Ken Nolan, Josh Hartnett, Ewan McGregor, Tom Sizemore and Eric Bana et al. 2002. Black Hawk Down. Culver City, CA: Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment. ISBN 9780767870627.

- Clarke, Walter and Robert Gosende. "Somalia: Can a Collapsed State Reconstitute Itself?" 129-158 in Rotberg, Robert I. 2003. State Failure and State Weakness in a Time of Terror. Cambridge, MA: World Peace Foundation. ISBN 9780815775744.

- Cran, William, and Will Lyman. 2001. Ambush in Mogadishu. Alexandria, VA: PBS Home Video. ISBN 9780780637450.

- Hirsch, John L., and Robert B. Oakley. 1995. Somalia and Operation Restore Hope: Reflections on Peacemaking and Peacekeeping. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 9781878379412.

- Kieh, George Klay, and Ida Rousseau Mukenge. 2002. Zones of Conflict in Africa Theories and Cases. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 9780313010835.

- Lyons, Terrence, and Ahmed I. Samatar. 1995. Somalia: State Collapse, Multilateral Intervention, and Strategies for Political Reconstruction. Brookings occasional papers. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. ISBN 9780815753513.

- Mayall, James. 1990. Nationalism and International Society. Cambridge studies in international relations, 10. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521373128.

- Moeller, Susan D. 1999. Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War, and Death. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9780415920971.

- Muravchik, Joshua. 2005. The Future of the United Nations: Understanding the Past to Chart a Way Forward. Washington, DC: AEI Press. ISBN 084466163X.

- Shawcross, William. 2000. Deliver us from Evil: Peacekeepers, Warlords, and a World of Endless Conflict. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684832333.

- Sklenka, Stephen D. 2007. Strategy, national interests, and means to an end. Carlisle papers in security strategy. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. ISBN 9781584873099. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

- Waal, Alex de. 2004. Islamism and its Enemies in the Horn of Africa. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Univ. Press. ISBN 9780253216793.

- Woodward, Peter. 1996. The Horn of Africa: State Politics and International Relations. International library of African studies, v. 6. London, UK: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781850437413.

External links

All links retrieved October 11, 2015.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου