John Henry is an American folk hero. An African American, he is said to have worked as a "steel-driving man"—a man tasked with hammering a steel drill into rock to make holes for explosives to blast the rock in constructing a railroad tunnel.

The story of John Henry is told in a classic blues folk song, which exists in many versions, and has been the subject of numerous stories, plays, books, and novels.[1][2]

Legend

According to legend, John Henry's prowess as a steel-driver was measured in a race against a steam-powered rock drilling machine, a race that he won only to die in victory with hammer in hand as his heart gave out from stress. Various locations, including Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia,[3] Lewis Tunnel in Virginia, and Coosa Mountain Tunnel in Alabama, have been suggested as the site of the contest.

The contest involved John Henry as the hammer man working in partnership with a shaker, who would hold a chisel-like drill against mountain rock, while the hammer man struck a powerful blow with a sledgehammer. Then the shaker would begin rocking and rolling: wiggling and rotating the drill to optimize its bite. The steam drill machine could drill but it could not shake the chippings away, so its bit could not drill further and frequently broke down.

History

The historical accuracy of many of the aspects of the John Henry legend are subject to debate.[1][2] According to researcher Scott Reynolds Nelson, the actual John Henry was born in 1848 in New Jersey and died of silicosis and not due to exhaustion of work.[4]

Several locations have been put forth for the tunnel on which John Henry died.

Big Bend Tunnel

Sociologist Guy B. Johnson investigated the legend of John Henry in the late 1920s. He concluded that John Henry might have worked on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway's (C&O Railway) Big Bend Tunnel but that "one can make out a case either for or against" it.[5][3] That tunnel was built near Talcott, West Virginia, from 1870 to 1872 (according to Johnson's dating), and named for the big bend in the Greenbrier River nearby.

Some versions of the song refer to the location of John Henry's death as "The Big Bend Tunnel on the C. & O."[3] In 1927, Johnson visited the area and found one man who said he had seen it.

This man, known as Neal Miller, told me in plain words how he had come to the tunnel with his father at 17, how he carried water and drills for the steel drivers, how he saw John Henry every day, and, finally, all about the contest between John Henry and the steam drill.

"When the agent for the steam drill company brought the drill here," said Mr. Miller, "John Henry wanted to drive against it. He took a lot of pride in his work and he hated to see a machine take the work of men like him.

"Well, they decided to hold a test to get an idea of how practical the steam drill was. The test went on all day and part of the next day.

"John Henry won. He wouldn't rest enough, and he overdid. He took sick and died soon after that."

Mr. Miller described the steam drill in detail. I made a sketch of it and later when I looked up pictures of the early steam drills, I found his description correct. I asked people about Mr. Miller's reputation, and they all said, "If Neal Miller said anything happened, it happened."[6]

When Johnson contacted Chief Engineer C. W. Johns of the C&O Railroad regarding Big Bend Tunnel, Johns replied that "no steam drills were ever used in this tunnel." When asked about documentation from the period, Johns replied that "all such papers have been destroyed by fire."[5]

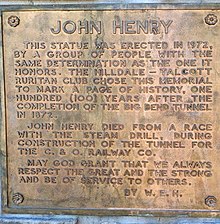

Talcott holds a yearly festival named for Henry, and a statue and memorial plaque have been placed along West Virginia Route 3 south of Talcott as it crosses over the Big Bend tunnel.[7] (Coords 37°38′56″N 80°46′04″W)

Lewis Tunnel

In the 2006 book Steel Drivin' Man: John Henry, the Untold Story of an American Legend, historian Scott Reynolds Nelson detailed his discovering documentation of a 19-year-old African-American man alternately referred to as John Henry, John W. Henry, or John William Henry in previously unexplored prison records of the Virginia Penitentiary. At the time, penitentiary inmates were hired out as laborers to various contractors, and this John Henry was notated as having headed the first group of prisoners to be assigned tunnel work. Nelson also discovered the C&O's tunneling records, which the company believed had been destroyed by fire. Henry, like many African Americans, might have come to Virginia to work on the clean-up of the battlefields after the Civil War. Arrested and tried for burglary, John Henry was in the first group of convicts released by the warden to work as leased labor on the C&O Railway.[8]:39

According to Nelson, objectionable conditions at the Virginia prison led the warden to believe that the prisoners, many of whom had been arrested on trivial charges, would be better clothed and fed if they were released as laborers to private contractors. (He subsequently changed his mind about this and became an opponent of the convict labor system.) In the C&O's tunneling records, Nelson found no evidence of a steam drill used in Big Bend Tunnel.[9]

The records Nelson found indicate that the contest took place 40 miles (64 km) away at the Lewis Tunnel, between Talcott and Millboro, Virginia, where prisoners did indeed work beside steam drills night and day.[10] Nelson also argues that the verses of the ballad about John Henry being buried near "the white house," "in the sand," somewhere that locomotives roar, mean that Henry's body was buried in a ditch behind the so-called white house of the Virginia State Penitentiary, which photos from that time indicate was painted white, and where numerous unmarked graves have been found.[11]

Prison records for John William Henry stopped in 1873, suggesting that he was kept on the record books until it was clear that he was not coming back and had died. Nelson stresses that John Henry would have been representative of the many hundreds of convict laborers who were killed in unknown circumstances tunneling through the mountains or who died shortly afterwards of silicosis from dust created by the drills and blasting.

Coosa Mountain Tunnel

There is another tradition that John Henry's famous race took place not in Virginia or West Virginia, but rather near Dunnavant, Alabama. Professor Johnson in the late 1920s received letters saying that John Henry worked on the A.G.S. Railway's Cruzee or Curzey Mountain Tunnel in 1882, and a third letter saying it was at Oak Mountain in 1887, but he discounted these reports after the A.G.S. told him that the railway had no such tunnel.[6] Retired chemistry professor and folklorist John Garst, of the University of Georgia, has argued that the contest happened at the Coosa Mountain Tunnel or the Oak Mountain Tunnel of the Columbus and Western Railway (now part of Norfolk Southern Railway) near Dunnavant on September 20, 1887.[12]

Based on documentation that corresponds with the account of C. C. Spencer, who claimed in the 1920s to have witnessed the contest, Garst speculates that John Henry may have been a man named Henry who was born a slave to P.A.L. Dabney, the father of the chief engineer of that railroad, in 1850.[12] Since 2007, the city of Leeds has honored John Henry's legend during an annual September festival, held on the third weekend in September, called the Leeds Downtown Folk Festival & John Henry Celebration.[13]

Garst and Nelson have debated the merits of their divergent research conclusions.[14] Other claims have been made over the years that place Henry and his contest in Kentucky or Jamaica.[15]

In other media

This article appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (June 2018) |

The tale of John Henry has been used as a symbol in many cultural movements, including labor movements[16] and the Civil Rights Movement.[17]

John Henry is a symbol of physical strength and endurance, of exploited labor, of the dignity of a human being against the degradations of the machine age, and of racial pride and solidarity. During World War II his image was used in U.S. government propaganda as a symbol of social tolerance and diversity.[18]

Film

In 1995, John Henry was portrayed in the movie Tall Tale by Roger Aaron Brown.

In the 1996 film Basquiat, the story of John Henry was told to Basquiat by his friend Benny as words of wisdom.

In 2018, it was announced that Dwayne Johnson would portray the character in a Netflix film, John Henry and the Statesmen. Development on the film has been delayed due to controversy over Johnson casting himself as the lead, with John Henry being a dark skinned black man.[19][20]

In 2020, Terry Crews played a modern-day adaptation of the legend in John Henry, in which he plays a former gang member who takes in two young teens who are on the run from his former gang leader, played by Ludacris. The film was released by Saban Films.[21]

Animation

In 1946, animator George Pal adapted the tale of John Henry into a short film titled John Henry and the Inky-Poo as part of his theatrical stop-motion Puppetoons series. The short is considered a milestone in American cinema as one of the first films to have a positive view of African-American folklore.[22][23]

In 1974, Nick Bosustow and David Adams co-produced an 11-minute animated short, The Legend of John Henry, for Paramount Pictures.[24]

The character later appeared in a Walt Disney Feature Animation short film, John Henry (2000). Directed by Mark Henn, plans for theatrical releases in 2000 and 2001 fell through after having a limited Academy Award qualifying run in Los Angeles,[25] a shorter version was released as the only new entry in direct-to-video release, Disney's American Legends (2002). It was eventually released in its original format as an interstitial on the Disney Channel, and later as part of the home video compilation Walt Disney Animation Studios Short Films Collection in 2015.

The 88th episode of season 5 of SpongeBob SquarePants, titled SpongeBob vs. The Patty Gadget, is a reference to the story of John Henry. It features SpongeBob competing against a machine called The Patty Gadget in an attempt to keep his job at The Krusty Krab.

Television

Danny Glover played the character in the series, Shelley Duvall's Tall Tales & Legends from 1985–1987. Duvall served as the series' creator, presenter, narrator, and executive producer. The show aired on Showtime Network as well as Disney Channel, and received a Primetime Emmy Award.

John Henry was mentioned in the season 7 premiere of Cheers.

The story of John Henry was prominently featured in a 2008 episode of the CBS crime drama, Cold Case.

In season 2 of the Smart Guy episode "TJ versus the machine", Floyd and TJ mentioned John Henry and his victory over the steam drill.

John Henry is briefly mentioned in an episode of 30 Rock, during season 6 titled “The Ballad of Kenneth Parcell”.

In Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles season 2 episode 10 John Henry is introduced both as the name of ZeiraCorp's A.I. and as the tale of a man who is unable to halt progress.

John Henry is also referenced in episode 4 of season 6 of the television show How I Met Your Mother, his legend briefly told through Marshall's song.

In the season 3 finale (Kimmy Bites an Onion!) of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt a version of The "Ballad of John Henry" is played with lyrics surmising the fight between Kimmy and a robot to become a crossing-guard. Like the legend, Kimmy gives her all to beat the robot and in doing so, effectively sacrifices her life.

Music

The story of John Henry is traditionally told through two types of songs: ballads, commonly called "The Ballad of John Henry", and "hammer songs" (a type of work song), each with wide-ranging and varying lyrics.[2][15] Some songs, and some early folk historian research, conflate the songs about John Henry with those of John Hardy, a West Virginian outlaw.[15] Ballads about John Henry's life typically contain four major components: a premonition by John Henry as a child that steel-driving would lead to his death, the lead-up to and the results of the legendary race against the steam hammer, Henry's death and burial, and the reaction of his wife.[15]

The well-known narrative ballad of "John Henry" is usually sung in an upbeat tempo. Hammer songs associated with the "John Henry" ballad, however, are not. Sung more slowly and deliberately, often with a pulsating beat suggestive of swinging the hammer, these songs usually contain the lines "This old hammer killed John Henry / but it won't kill me." Nelson explains that:

... workers managed their labor by setting a "stint," or pace, for it. Men who violated the stint were shunned ... Here was a song that told you what happened to men who worked too fast: they died ugly deaths; their entrails fell on the ground. You sang the song slowly, you worked slowly, you guarded your life, or you died.[8]:32

There is some controversy among scholars over which came first, the ballad or the hammer songs. Some scholars have suggested that the "John Henry" ballad grew out of the hammer songs, while others believe that the two were always entirely separate.

Songs featuring the story of John Henry have been recorded by many musical artists and bands of different ethnic backgrounds. These include:

- McDowell’s version is included on the ‘’Ann Arbor Blues Festival 1969: Vols 1&2’’ 2019 release.[26]

- Doc Watson

- Burl Ives

- Josh White[27]

- Bill Monroe

- Dave Van RonkDave Van Ronk Sings Ballads, Blues, and a Spiritual

- Kabir Suman

- Hemanga Biswas

- Johnny Cash[28]

- Drive-By Truckers (on their The Dirty South album)

- Joe Bonamassa[15]

- Furry Lewis[2]

- Big Bill Broonzy[2]

- Pink Anderson[15]

- Fiddlin' John Carson[15]

- Uncle Dave Macon[15]

- J. E. Mainer[15]

- Leon Bibb[15]

- Lead Belly[15]

- Woody Guthrie[15]

- Paul Robeson[18]

- Pete Seeger[18]

- Van Morrison[18]

- Bruce Springsteen[18]

- Gillian Welch[18]

- Cuff the Duke[18]

- Ramblin' Jack Elliott[15]

- Jerry Reed[15]

- Jerry Lee Lewis[15]

- Merle Travis, Jimmy Dean[29]

- Harry Belafonte[30]

- Mississippi John Hurt (as "Spike Driver Blues")[31][32]

- Lonnie Donegan[33]

- Jack Warshaw[34]

- Jason Molina[35]

- Trail West[36]

- Stafford Galli[37]

- John Fahey[38]

- Steve Earle

- Justin Townes Earle[39]

- The Limeliters

- Cecile McLorin Salvant[40]

- Those Poor Bastards[41]

- Marcus Martin[42]

- Emily Saliers

- Grayson & Whitter[43]

The story also inspired the Aaron Copland's orchestral composition "John Henry" (1940, revised 1952), the 1994 chamber music piece Come Down Heavy by Evan Chambers and the 2009 chamber music piece Steel Hammer by the composer Julia Wolfe.[44][45]

They Might Be Giants named their fifth studio album after John Henry.

The American cowpunk band Nine Pound Hammer is named after the traditional description of the hammer John Henry wielded.

Bengalee singer-songwriter and musician Hemanga Biswas (1912-1987), considered to be as the Father of the Indian People's Theater Association Movement in Assam inspired by ’John Henry’, the American ballad translated the song in Bengali as well as Assamese language and also composed its music for which he was well recognized among the masses.[46][47] Bangladeshi mass singer Fakir Alamgir later covered Biswas' version of the song.[48][49]

Literature

Henry is the subject of the 1931 Roark Bradford novel John Henry, illustrated by noted woodcut artist J. J. Lankes. The novel was adapted into a stage musical in 1940, starring Paul Robeson in the title role.[2] According to Steven Carl Tracy, Bradford's works were influential in broadly popularizing the John Henry legend beyond railroad and mining communities and outside of African American oral histories.[2] In a 1933 article published in The Journal of Negro Education, Bradford's John Henry was criticized for "making over a folk-hero into a clown."[50] A 1948 obituary for Bradford described John Henry as "a better piece of native folklore than Paul Bunyan."[51]

Ezra Jack Keats's John Henry: An American Legend, published in 1965, is a notable picture book chronicling the history of John Henry and portraying him as the "personification of the medieval Everyman who struggles against insurmountable odds and wins."[17]

Colson Whitehead's 2001 novel John Henry Days uses the John Henry myth as story background. Whitehead fictionalized the John Henry Days festival in Talcott, West Virginia and the release of the John Henry postage stamp in 1996.[52]

The textbook titled American Music: A Panorama by Daniel Kingman displays the lyrics of the ballad titled "John Henry", explores its style and relates the history of the hero. That's in Chapter 2: The African–American Tradition.

In the comic series DC: The New Frontier, an African American man named John Wilson becomes a vigilante in order to battle the Ku Klux Klan after his family is lynched. He names himself after John Henry and even uses John Henry's weapons/tools, two iron sledgehammers. For three months, he plagues the Klan in Tennessee. Unfortunately, he was wounded, discovered by a white girl, was caught by the Klan, and was burned alive.

The DC Comics superhero Steel's civilian name, "John Henry Irons," is inspired by John Henry.[53] The story of John Henry is further referenced by Steel's weapon of choice, a sledgehammer. In DC's Super Friends #21 (January 2010), Superman encountered the actual John Henry after being placed in the folk tale by the Queen of Fables.

Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky is a juvenile fantasy novel about seventh grader Tristan Strong who travels to another world and encounters black American gods. These include Br'er Rabbit, Anansi, and John Henry.

He appears as a character in Peter Clines' novel Paradox Bound.

He makes an appearance in the IDW Publishing miniseries The Transformers: Hearts of Steel

United States postage stamp

In 1996, the US Postal Service issued a John Henry postage stamp. It was part of a set honoring American folk heroes that included Paul Bunyan, Pecos Bill and Casey at the Bat.[54]

Video games

John Henry was featured as a fictional character in the 2014 video game Wasteland 2. The story is referenced by various NPCs throughout the game and is also available in full as a series of in game books which tell the story of the competition between John Henry and a contingent of robotic workers.[55]

He also appeared as a playable character in the 3DS game Code Name: S.T.E.A.M..

In the story of Team Fortress 2 comics, he was the first Heavy of the original BLU team.[56]

In Civilization IV, the quote "Before that steam drill shall beat me down, I'll die with my hammer in my hand." appears when steel is researched.[57]

The Big Bend Tunnel is a location of the multiplayer videogame Fallout 76, set in Appalachia region. The story surrounding the Miner Miracles quest is a reference to John Henry's competition.

See also

References

- "Tech Quotes from Civilization IV – Industrial Era Technologies". levelskip.com. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

Further reading

- Johnson, Guy B. (1929). John Henry: Tracking Down a Negro Legend. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press

- Chappell, Louis W. (1933). John Henry; A Folk-Lore Study. Reprinted 1968. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press

- Keats, Ezra Jack (1965). John Henry, An American Legend. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Williams, Brett (1983). John Henry: A Bio-Bibliography by Brett Williams. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press

- Nelson, Scott. "Who Was John Henry? Railroad Construction, Southern Folklore, and the Birth of Rock and Roll", Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas Summer 2005 2(2): 53–80; doi:10.1215/15476715-2-2-53

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Henry. |

- John Henry at The Seeger Sessions at the Wayback Machine (archived 13 October 2016)

- Lyrics to various versions of "John Henry"

- Survey of books about the legend of John Henry

- Essay on resistance and rebellion in the legend of John Henry

- John Henry bibliography compiled by the Archive of Folk Culture staff at the Library of Congress

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. WV-93, "Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad, Great Bend Tunnel, Talcott, Summers County, WV"

"John Henry in Leeds" Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, Leeds Folk Festival

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου